Complexities in diagnosing inherited retinal diseases

The overlapping challenges of inherited retinal diseases

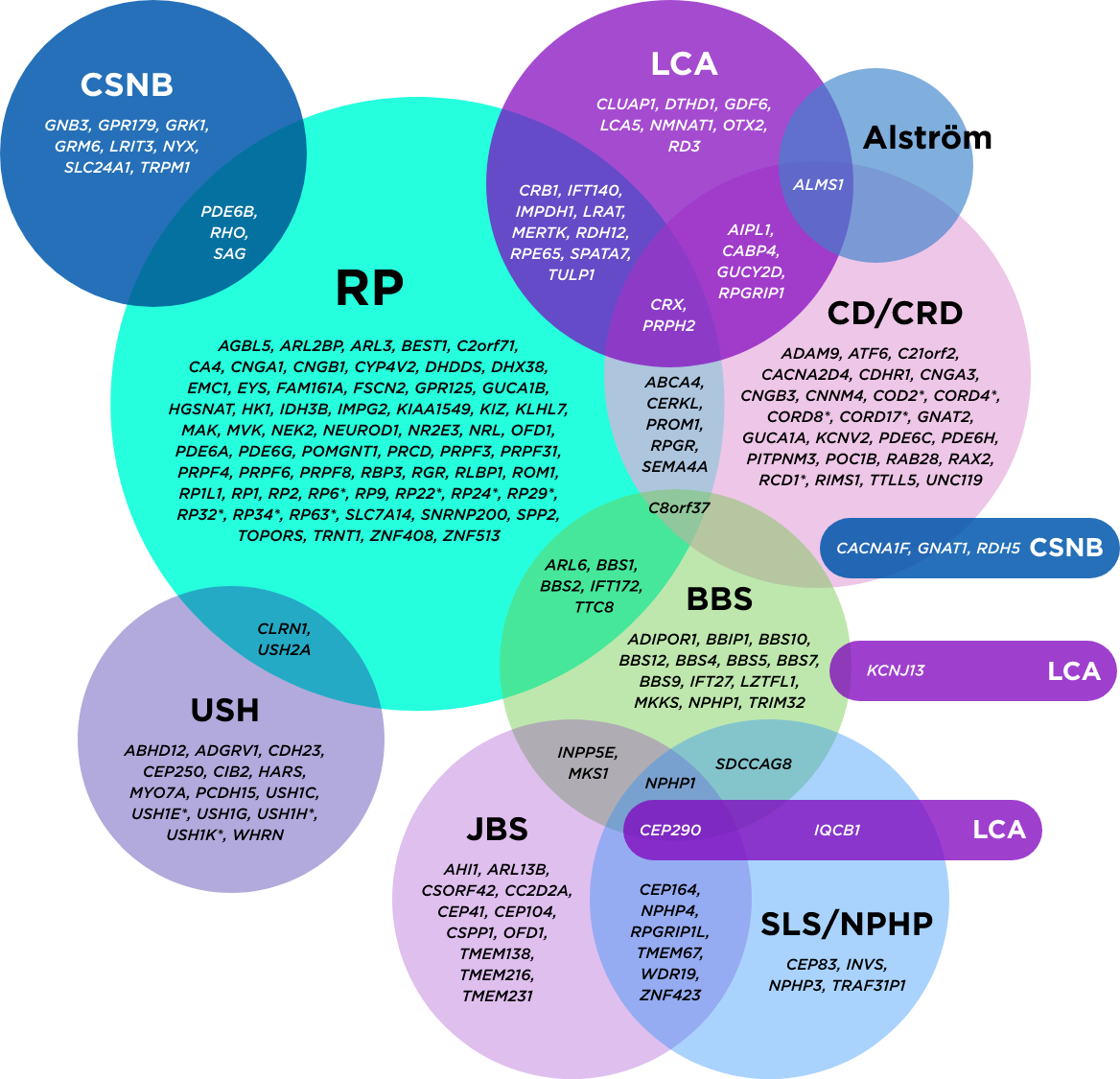

The genetic heterogeneity of inherited retinal diseases can make it challenging to reach a specific diagnosis. A single gene may even be associated with multiple phenotypes

*Mapped genetic loci without an identified gene, as of 2019.

©2021 American Academy of Ophthalmology. Reproduced with permission.

AAO=American Academy of Ophthalmology; BBS=Bardet-Biedl syndrome; CD=cone dystrophy; CRD=cone-rod dystrophy; CSNB=congenital stationary night blindness; JBS=Joubert syndrome; LCA=Leber congenital amaurosis; NPHP=nephronophthisis; RP=retinitis pigmentosa; SLS=Sjögren-Larsson syndrome; USH=Usher syndrome.

Genetic testing further supports clinical findings and has become the standard for reaching a precise diagnosis. An accurate, definitive diagnosis helps inform the best course of action for potential medical management.

Inherited retinal diseases: signs, symptoms, and prevalence

Disclaimer: All prevalence rates are global estimates and may vary across regions.

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP)

- Variants in over 100 genes are known to cause RP

Signs/symptoms may include

- Nyctalopia (earliest symptom)

- Primary degeneration affects photoreceptor rods, causing night blindness as the first clinical manifestation. Degeneration advances from the periphery toward the fovea, progressively decreasing the visual field and leading to tunnel vision. In the end stages of a typical rod-cone dystrophy, cones are also affected, leading to the loss of visual acuity

Age of symptom onset

Childhood or adulthood

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 3,000

Subsets

- Autosomal dominant: Approximately 30% to 40% of cases

- Autosomal recessive: Approximately 50% to 60% of cases

- X-linked: Approximately 5% to 15% of cases; particularly severe in males, with onset in early childhood and characterised by rapid progression of vision loss resulting in legal blindness by the end of the third decade here

Usher syndrome (USH)

- Differentiation into 3 types (USH1, USH2, USH3) according to symptom relevance/clinical presentation

- Variants in 10 genes are known to cause Usher syndrome

Signs/symptoms may include

This disorder is characterised by the combination of:

- A degenerative vision loss condition, known as RP

- Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL)

- Sometimes, vestibular dysfunction

Age of symptom onset

- Hearing symptoms usually appear at birth in USH1 and USH2, while hearing loss symptoms usually appear by late childhood or adolescence in USH3. Vision loss appears in childhood in USH1, and usually in adolescence in USH2 and USH3

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 6,000

Stargardt disease

- Variants in 2 genes are known to cause Stargardt disease

Signs/symptoms may include

- Slow, progressive loss of central vision

- Nyctalopia

- Colour blindness

- Heterogeneous symptomatology and progression

Age of symptom onset varies

- Childhood

- Early adulthood

- Late adulthood, when the average age at onset of symptoms is approximately 55 years (misdiagnosis with age-related macular degeneration possible)

Estimated prevalence

- Up to 1 in 8,000

- Most common cause of juvenile macular dystrophy

Cone-rod dystrophy (CRD)

- Variants in about 30 genes are known to cause cone-rod dystrophy

Signs/symptoms may include

- Decreased visual acuity

- Photophobia

- Colour blindness

- Scotomas

- Loss of peripheral vision

- Legal blindness by mid-adulthood

Age of symptom onset

Childhood

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 30,000

Achromatopsia (ACHM)

- Variants in 6 genes are known to cause achromatopsia

Signs/symptoms may include

- Decreased visual acuity

- Loss of peripheral vision

- Involuntary eye movements

- Photophobia

- Partial or total loss of colour vision

- Legal blindness by mid-adulthood

Age of symptom onset

At birth or in early infancy

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 30,000

Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA)

- Variants in 38 genes are known to cause Leber congenital amaurosis

Signs/symptoms may include

- Vision loss (at birth to early infancy)

- Photophobia

- Nystagmus

- Hyperopia

- Keratoconus

- Amaurotic pupils

Age of symptom onset

At infancy

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 30,000

Choroideraemia (CHM)

- Variants in the CHM gene cause choroideraemia

Signs/symptoms may include

- Progressive atrophy of the retina and choroid

- Nyctalopia in early childhood

- Progressive loss of peripheral visual field and visual acuity

- All individuals will develop blindness, most commonly in late adulthood

Age of symptom onset

Early childhood

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 50,000

Bardet-Biedl syndrome (BBS)

- Variants in 26 genes are known to cause Bardet-Biedl syndrome

Signs/symptoms may include

- Nyctalopia

- Tunnel vision

- Blurred central vision

- Blindness (adolescence to early adulthood)

Non-ophthalmic signs/symptoms

- Renal malformations

- Obesity

- Postaxial polydactyly

- Hypogonadism

- Developmental delays

Age of symptom onset

Symptoms emerge throughout infancy, childhood and young adulthood

Estimated prevalence

Up to 1 in 100,000—1 in 140,000 people in North America and 1 in 125,000 – 1 in 160,000 people in Europe

Going beyond the clinical signs and symptoms

Clinical signs and symptoms may raise suspicion that your patient has an inherited retinal disease. Your patient may express additional concerns during their exam, such as:

- Worry about inherited retinal disease being passed down to others in their family

- Challenges in daily activities such as driving, shopping, or reading

- Issues with mobility such as crossing the street or walking up stairs

- Difficulty working or finding new employment

- Problems interacting with family and friends

- Overwhelming fear about going blind

- Feelings of frustration or anxiety

Family history alone doesn’t tell the full story

Obtaining a thorough family history can help assess your patient’s risk or identify a likely pattern of inheritance. Although the majority of patients who have no known family history have autosomal recessive diseases, some may have dominant diseases due to a de novo pathogenic variant. Others may have a dominant disease exhibiting incomplete penetrance. And still there are those who may have no known family history of X-linked diseases.

Genetic testing can help identify the genetic basis of the disease in 56–76% of patients with different forms of IRDs.

Early testing matters

Early genetic testing may allow you to detect genetic variants responsible for inherited retinal diseases more timely. This enables you and your patients’ care teams to create a more comprehensive plan for the future.

New answers may help your patients move forward in their lives, from career and family planning to speaking with family members who may also benefit from genetic testing.

If you suspect an inherited retinal disease. . .

- Establish clinical diagnosis of an inherited retinal disease

- Assess visual function and plan visual rehabilitation

- Confirm the genetic diagnosis and partner with a genetic counsellor to guide appropriate care for individuals with IRDs.

- Monitor disease progression and plan for therapeutic interventions where possible

Taking these proactive steps, including testing your patients’ genes for an inherited retinal disease, can help them get closer to the answers they need.

Discover the importance of testing and retesting and how it can help you better support your patients with their eye care.

Stay informed

We would like to stay in touch with you to share updates on the latest medical and scientific developments, as well as resources to complement your patient care. Additionally, we'll keep you informed about both local and international events, including medical education accredited learning resources.